SLSA is a specification for describing and incrementally improving supply chain

security, established by industry consensus. It is organized into a series of

levels that describe increasing security guarantees.

This is version 1.0 of the SLSA specification, which defines the SLSA

levels. For other versions, use the chooser to

the rightat the bottom of this section. For

the recommended attestation formats, including provenance, see “Specifications”

in the menu at the top.

About this release candidate

This release candidate is a preview of version 1.0. It contains all

anticipated concepts and major changes for v1.0, but there are still outstanding

TODOs and cleanups. We expect to cover all TODOs and address feedback before the

1.0 final release.

Known issues:

-

TODO: Use consistent terminology throughout the site: “publish” vs

“release”, “publisher” vs “maintainer” vs “developer”, “consumer” vs

“ecosystem” vs “downstream system”, “build” vs “produce.

-

Verifying artifacts and setting expectations are still in flux. We would

like feedback on whether to move these parts out of the build track.

Understanding SLSA

These sections provide an overview of SLSA, how it helps protect against common supply chain attacks, and common use cases. If you’re new to SLSA or supply chain security, start here.

Core specification

These sections describe SLSA’s security levels and requirements for each track. If you want to achieve SLSA a particular level, these are the requirements you’ll need to meet.

| Section |

Description |

| Terminology |

Terminology and model used by SLSA |

| Security levels |

Overview of SLSA’s tracks and levels, intended for all audiences |

| Producing artifacts |

Detailed technical requirements for producing software artifacts, intended for system implementers |

| Verifying build systems |

Guidelines for securing SLSA Build L3+ builders, intended for system implementers |

| Verifying artifacts |

Guidance for verifying software artifacts and their SLSA provenance, intended for system implementers and software consumers |

| Threats & mitigations |

Detailed information about specific supply chain attacks and how SLSA helps |

These sections include the concrete schemas for SLSA attestations. The Provenance and VSA formats are recommended, but not required by the specification.

| Section |

Description |

| General model |

General attestation mode |

| Provenance |

Suggested provenance format and explanation |

| VSA |

Suggested VSA format and explanation |

How to SLSA

These instructions tell you how to apply the core SLSA specification to use SLSA in your specific situation.

What's new in SLSA v1.0

SLSA v1.0 represents changes made in response to feedback from the SLSA

community and early adopters of SLSA v0.1. Overall, these changes

prioritize simplicity and practicality.

Check back here for a detailed v1.0 changelog with the official 1.0 release!

Until then, see the following for more information about what’s new:

About SLSA

This section is an introduction to SLSA and its concepts. If you’re new

to SLSA, start here!

What is SLSA?

SLSA is a set of incrementally adoptable guidelines for supply chain security,

established by industry consensus. The specification set by SLSA is useful for

both software producers and consumers: producers can follow SLSA’s guidelines to

make their software supply chain more secure, and consumers can use SLSA to make

decisions about whether to trust a software package.

SLSA offers:

- A common vocabulary to talk about software supply chain security

- A way to secure your incoming supply chain by evaluating the trustworthiness of the artifacts you consume

- An actionable checklist to improve your own software’s security

- A way to measure your efforts toward compliance with forthcoming

Executive Order standards in the Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF)

Why SLSA is needed

High profile attacks like those against SolarWinds or Codecov have exposed the kind of supply

chain integrity weaknesses that may go unnoticed, yet quickly become very

public, disruptive, and costly in today’s environment when exploited. They’ve

also shown that there are inherent risks not just in code itself, but at

multiple points in the complex process of getting that code into software

systems—that is, in the software supply chain. Since these attacks are on

the rise and show no sign of decreasing, a universal framework for hardening the

software supply chain is needed, as affirmed by the

U.S. Executive Order on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity.

Security techniques for vulnerability detection and analysis of source code are

essential, but are not enough on their own. Even after fuzzing or vulnerability

scanning is completed, changes to code can happen, whether unintentionally or

from insider threats or compromised accounts. Risk for code modification exists at

each link in a typical software supply chain, from source to build through

packaging and distribution. Any weaknesses in the supply chain undermine

confidence in whether the code that you run is actually the code that you

scanned.

SLSA is designed to support automation that tracks code handling from source

to binary, protecting against tampering regardless of the complexity

of the software supply chain. As a result, SLSA increases trust that the

analysis and review performed on source code can be assumed to still apply to

the binary consumed after the build and distribution process.

SLSA in layperson’s terms

There has been a lot of discussion about the need for “ingredient labels” for

software—a “software bill of materials” (SBOM) that tells users what is in their

software. Building off this analogy, SLSA can be thought of as all the food

safety handling guidelines that make an ingredient list credible. From standards

for clean factory environments so contaminants aren’t introduced in packaging

plants, to the requirement for tamper-proof seals on lids that ensure nobody

changes the contents of items sitting on grocery store shelves, the entire food

safety framework ensures that consumers can trust that the ingredient list

matches what’s actually in the package they buy.

Likewise, the SLSA framework provides this trust with guidelines and

tamper-resistant evidence for securing each step of the software production

process. That means you know not only that nothing unexpected was added to the

software product, but also that the ingredient label itself wasn’t tampered with

and accurately reflects the software contents. In this way, SLSA helps protect

against the risk of:

- Code modification (by adding a tamper-evident “seal” to code after

source control)

- Uploaded artifacts that were not built by the expected CI/CD system (by marking

artifacts with a factory “stamp” that shows which build service created it)

- Threats against the build system (by providing “manufacturing facility”

best practices for build system services)

For more exploration of this analogy, see the blog post

SLSA + SBOM: Accelerating SBOM success with the help of SLSA.

Who is SLSA for?

In short: everyone involved in producing and consuming software, or providing

infrastructure for software.

Software producers, such as a development team or open

source maintainers. SLSA gives you protection against insider risk and tampering

along the supply chain to your consumers, increasing confidence that the

software you produce reaches your consumers as you intended.

Software consumers, such as a development team using open source packages, a

government agency using vendored software, or a CISO judging organizational

risk. SLSA gives you a way to judge the security practices of the software you

rely on and be sure that what you receive is what you expected.

Infrastructure providers, who provide infrastructure such as an ecosystem

package manager, build platform, or CI/CD system. As the bridge between the

producers and consumers, your adoption of SLSA enables a secure software supply

chain between them.

How SLSA works

We talk about SLSA in terms of tracks and levels.

A SLSA track focuses on a particular aspect of a supply chain, such as the Build

Track. SLSA v1.0 consists of only a single track (Build), but future versions of

SLSA will add tracks that cover other parts of the software supply chain, such

as how source code is managed.

Within each track, ascending levels indicate increasingly hardened security

practices. Higher levels provide better guarantees against supply chain threats,

but come at higher implementation costs. Lower SLSA levels are designed to be

easier to adopt, but with only modest security guarantees. SLSA 0 is sometimes

used to refer to software that doesn’t yet meet any SLSA level. Currently, the

SLSA Build Track encompasses Levels 1 through 3, but we envision higher levels

to be possible in future revisions.

The combination of tracks and levels offers an easy way to discuss whether

software meets a specific set of requirements. By referring to an artifact as

meeting SLSA Build Level 3, for example, you’re indicating in one phrase that

the software artifact was built following a set of security practices that

industry leaders agree protect against particular supply chain compromises.

What SLSA doesn’t cover

SLSA is only one part of a thorough approach to supply chain security. There

are several areas outside SLSA’s current framework that are nevertheless

important to consider together with SLSA such as:

- Code quality: SLSA does not tell you whether the developers writing the

source code followed secure coding practices.

- Developer trust: SLSA cannot tell you whether a developer is

intentionally writing malicious code. If you trust a developer to write

code you want to consume, though, SLSA can guarantee that the code will

reach you without another party tampering with it.

- Transitive trust for dependencies: the SLSA level of an artifact is

independent of the level of its dependencies. You can use SLSA recursively to

also judge an artifact’s dependencies on their own, but there is

currently no single SLSA level that applies to both an artifact and its

transitive dependencies together. For a more detailed explanation of why,

see the FAQ.

Supply chain threats

Attacks can occur at every link in a typical software supply chain, and these

kinds of attacks are increasingly public, disruptive, and costly in today’s

environment.

This section is an introduction to possible attacks throughout the supply chain and how

SLSA can help. For a more technical discussion, see Threats & mitigations.

Summary

SLSA’s primary focus is supply chain integrity, with a secondary focus on

availability. Integrity means protection against tampering or unauthorized

modification at any stage of the software lifecycle. Within SLSA, we divide

integrity into source integrity vs build integrity.

Source integrity: Ensure that all changes to the source code reflect the

intent of the software producer. Intent of an organization is difficult to

define, so SLSA approximates this as approval from two authorized

representatives.

Build integrity: Ensure that the package is built from the correct,

unmodified sources and dependencies according to the build recipe defined by the

software producer, and that artifacts are not modified as they pass between

development stages.

Availability: Ensure that the package can continue to be built and

maintained in the future, and that all code and change history is available for

investigations and incident response.

Real-world examples

TODO: Update this for v1.0.

Many recent high-profile attacks were consequences of supply chain integrity vulnerabilities, and could have been prevented by SLSA’s framework. For example:

|

| Integrity threat

| Known example

| How SLSA can help

|

| A

| Submit unauthorized change (to source repo)

| Linux hypocrite commits: Researcher attempted to intentionally introduce vulnerabilities into the Linux kernel via patches on the mailing list.

| Two-person review caught most, but not all, of the vulnerabilities.

|

| B

| Compromise source repo

| PHP: Attacker compromised PHP's self-hosted git server and injected two malicious commits.

| A better-protected source code platform would have been a much harder target for the attackers.

|

| C

| Build from modified source (not matching source repo)

| Webmin: Attacker modified the build infrastructure to use source files not matching source control.

| A SLSA-compliant build server would have produced provenance identifying the actual sources used, allowing consumers to detect such tampering.

|

| D

| Use compromised dependency (i.e. A-H, recursively)

| event-stream: Attacker added an innocuous dependency and then later updated the dependency to add malicious behavior. The update did not match the code submitted to GitHub (i.e. attack F).

| Applying SLSA recursively to all dependencies would have prevented this particular vector, because the provenance would have indicated that it either wasn't built from a proper builder or that the source did not come from GitHub.

|

| E

| Compromise build process

| SolarWinds: Attacker compromised the build platform and installed an implant that injected malicious behavior during each build.

| Higher SLSA levels require stronger security controls for the build platform, making it more difficult to compromise and gain persistence.

|

| F

| Upload modified package (not matching build process)

| CodeCov: Attacker used leaked credentials to upload a malicious artifact to a GCS bucket, from which users download directly.

| Provenance of the artifact in the GCS bucket would have shown that the artifact was not built in the expected manner from the expected source repo.

|

| G

| Compromise package repo

| Attacks on Package Mirrors: Researcher ran mirrors for several popular package repositories, which could have been used to serve malicious packages.

| Similar to above (F), provenance of the malicious artifacts would have shown that they were not built as expected or from the expected source repo.

|

| H

| Use compromised package

| Browserify typosquatting: Attacker uploaded a malicious package with a similar name as the original.

| SLSA does not directly address this threat, but provenance linking back to source control can enable and enhance other solutions.

|

|

| Availability threat

| Known example

| How SLSA can help

|

| D

| Dependency becomes unavailable

| Mimemagic: Producer intentionally removes package or version of package from repository with no warning. Network errors or service outages may also make packages unavailable temporarily.

| SLSA does not directly address this threat.

|

A SLSA level helps give consumers confidence that software has not been tampered

with and can be securely traced back to source—something that is difficult, if

not impossible, to do with most software today.

Use cases

SLSA protects against tampering during the software supply chain, but how?

The answer depends on the use case in which SLSA is applied. Below

describe the three main use cases for SLSA.

Applications of SLSA

First party

Reducing risk within an organization from insiders and compromised accounts

In its simplest form, SLSA can be used entirely within an organization to reduce

risk from internal sources. This is the easiest case in which to apply SLSA

because there is no need to transfer trust across organizational boundaries.

Example ways an organization might use SLSA internally:

- A small company or team uses SLSA to ensure that the code being deployed to

production in binary form is the same one that was tested and reviewed in

source form.

- A large company uses SLSA to require two person review for every production

change, scalably across hundreds or thousands of employees/teams.

- An open source project uses SLSA to ensure that compromised credentials

cannot be abused to release an unofficial package to a package repostory.

Case study: Google (Binary Authorization for Borg)

Open source

Reducing risk from consuming open source software

SLSA can also be used to reduce risk for consumers of open source software. The

focus here is to map built packages back to their canonical sources and

dependencies. In this way, consumers need only trust a small number of secure

build systems rather than the many thousands of developers with upload

permissions across various packages.

Example ways an open source ecosystem might use SLSA to protect users:

- At upload time, the package registry rejects the package if it was not built

from the canonical source repository.

- At download time, the packaging client rejects the package if it was not

built by a trusted builder.

Case study: SUSE

Vendors

Reducing risk from consuming vendor provided software and services

Finally, SLSA can be used to reduce risk for consumers of vendor provided

software and services. Unlike open source, there is no canonical source

repository to map to, so instead the focus is on trustworthiness of claims made

by the vendor.

Example ways a consumer might use SLSA for vendor provided software:

- Prefer vendors who make SLSA claims and back them up with credible evidence.

- Require a vendor to implement SLSA as part of a contract.

- Require a vendor to be SLSA certified from a trusted third-party auditor.

Guiding principles

This section is an introduction to the guiding principles behind SLSA’s design

decisions.

Trust systems, verify artifacts

Establish trust in a small number of systems—such as change management, build,

and packaging systems—and then automatically verify the many artifacts

produced by those systems.

Reasoning: Trusted computing bases are unavoidable—there’s no choice but

to trust some systems. Hardening and verifying systems is difficult and

expensive manual work, and each trusted system expands the attack surface of the

supply chain. Verifying that an artifact is produced by a trusted system,

though, is easy to automate.

To simultaniously scale and reduce attack surfaces, it is most efficient to trust a limited

numbers of systems and then automate verification of the artifacts produced by those systems.

The attack surface and work to establish trust does not scale with the number of artifacts produced,

as happens when artifacts each use a different trusted system.

Benefits: Allows SLSA to scale to entire ecosystems or organizations with a near-constant

amount of central work.

Example

A security engineer analyzes the architecture and implementation of a build

system to ensure that it meets the SLSA Build Track requirements. Following the

analysis, the public keys used by the build system to sign provenance are

“trusted” up to the given SLSA level. Downstream systems verify the provenance

signed by the public key to automatically determine that an artifact meets the

SLSA level.

Corollary: Minimize the number of trusted systems

A corollary to this principle is to minimize the size of the trusted computing

base. Every system we trust adds attack surface and increases the need for

manual security analysis. Where possible:

- Concentrate trust in shared infrastructure. For example, instead of each

team within an organization maintaining their own build system, use a

shared build system. Hardening work can be shared across all teams.

- Remove the need to trust components. For example, use end-to-end signing

to avoid the need to trust intermediate distribution systems.

Trust code, not individuals

Securely trace all software back to source code rather than trust individuals who have write access to package registries.

Reasoning: Code is static and analyzable. People, on the other hand, are prone to mistakes,

credential compromise, and sometimes malicious action.

Benefits: Removes the possibility for a trusted individual—or an

attacker abusing compromised credentials—to tamper with source code

after it has been committed.

Prefer attestations over inferences

Require explicit attestations about an artifact’s provenance; do not infer

security properties from a system’s configurations.

Reasoning: Theoretically, access control can be configured so that the only path from

source to release is through the official channels: the CI/CD system pulls only

from the proper source, package registry allows access only to the CI/CD system,

and so on. We might infer that we can trust artifacts produced by these systems

based on the system’s configuration.

In practice, though, these configurations are almost impossible to get right and

keep right. There are often over-provisioning, confused deputy problems, or

mistakes. Even if a system is configured properly at one moment, it might not

stay that way, and humans almost always end up getting in the access control

lists.

Access control is still important, but SLSA goes further to provide defense in depth: it requires proof in

the form of attestations that the package was built correctly.

Benefits: The attestation removes intermediate systems from the trust base and ensures that

individuals who are accidentally granted access do not have sufficient permission to tamper with the package.

Frequently asked questions

Q: Why is SLSA not transitive?

SLSA Build levels only cover the trustworthiness of a single build, with no

requirements about the build levels of transitive dependencies. The reason for

this is to make the problem tractable. If a SLSA Build level required

dependencies to be the same level, then reaching a level would require starting

at the very beginning of the supply chain and working forward. This is

backwards, forcing us to work on the least risky component first and blocking

any progress further downstream. By making each artifact’s SLSA rating

independent from one another, it allows parallel progress and prioritization

based on risk. (This is a lesson we learned when deploying other security

controls at scale throughout Google.) We expect SLSA ratings to be composed to

describe a supply chain’s overall security stance, as described in the case

study vision.

Q: What about reproducible builds?

When talking about reproducible builds, there

are two related but distinct concepts: “reproducible” and “verified

reproducible.”

“Reproducible” means that repeating the build with the same inputs results in

bit-for-bit identical output. This property

provides

many

benefits,

including easier debugging, more confident cherry-pick releases, better build

caching and storage efficiency, and accurate dependency tracking.

“Verified reproducible” means using two or more independent build systems to

corroborate the provenance of a build. In this way, one can create an overall

system that is more trustworthy than any of the individual components. This is

often

suggested

as a solution to supply chain integrity. Indeed, this is one option to secure

build steps of a supply chain. When designed correctly, such a system can

satisfy all of the SLSA Build level requirements.

That said, verified reproducible builds are not a complete solution to supply

chain integrity, nor are they practical in all cases:

- Reproducible builds do not address source, dependency, or distribution

threats.

- Reproducers must truly be independent, lest they all be susceptible to the

same attack. For example, if all rebuilders run the same pipeline software,

and that software has a vulnerability that can be triggered by sending a

build request, then an attacker can compromise all rebuilders, violating the

assumption above.

- Some builds cannot easily be made reproducible, as noted above.

- Closed-source reproducible builds require the code owner to either grant

source access to multiple independent rebuilders, which is unacceptable in

many cases, or develop multiple, independent in-house rebuilders, which is

likely prohibitively expensive.

Therefore, SLSA does not require verified reproducible builds directly. Instead,

verified reproducible builds are one option for implementing the requirements.

For more on reproducibility, see

Hermetic, Reproducible, or Verifiable?

Q: How does SLSA relate to in-toto?

in-toto is a framework to secure software supply chains

hosted at the Cloud Native Computing Foundation. The in-toto

specification provides a generalized workflow to secure different steps in a

software supply chain. The SLSA specification recommends

in-toto attestations as the vehicle to

express Provenance and other attributes of software supply chains. Thus, in-toto

can be thought of as the unopinionated layer to express information pertaining

to a software supply chain, and SLSA as the opinionated layer specifying exactly

what information must be captured in in-toto metadata to achieve the guarantees

of a particular level.

in-toto’s official implementations written in

Go,

Java, and

Rust include support for generating

SLSA Provenance metadata. These APIs are used in other tools generating SLSA

Provenance such as Sigstore’s cosign, the SLSA GitHub Generator, and the in-toto

Jenkins plugin.

Future directions

The initial draft version (v0.1) of SLSA had a larger scope including

protections against tampering with source code and a higher level of build

integrity (Build L4). This section collects some early thoughts on how SLSA

might evolve in future versions to re-introduce those notions and add other

additional aspects of automatable supply chain security.

Build track

Build L4

A build L4 could include further hardening of the build service and enabling

corraboration of the provenance, for example by providing complete knowledge of

the build inputs.

The initial draft version (v0.1) of SLSA defined a “SLSA 4” that included the

following requirements, which may or may not be part of a future Build L4:

- Pinned dependencies, which guarantee that each build runs on exactly the

same set of inputs.

- Hermetic builds, which guarantee that no extraneous dependencies are used.

- All dependencies listed in the provenance, which enables downstream systems

to recursively apply SLSA to dependencies.

- Reproducible builds, which enable other systems to corroborate the

provenance.

Source track

A Source track could provide protection against tampering of the source code

prior to the build.

The initial draft version (v0.1)

of SLSA included the following source requirements, which may or may not

form the basis for a future Source track:

- Strong authentication of author and reviewer identities, such as 2-factor

authentication using a hardware security key, to resist account and

credential compromise.

- Retention of the source code to allow for after-the-fact inspection and

future rebuilds.

- Mandatory two-person review of all changes to the source to prevent a single

compromised actor or account from introducing malicious changes.

Terminology

Before diving into the SLSA Levels, we need to establish a core set

of terminology and models to describe what we’re protecting.

Software supply chain

SLSA’s framework addresses every step of the software supply chain - the

sequence of steps resulting in the creation of an artifact. We represent a

supply chain as a directed acyclic graph of sources, builds, dependencies, and

packages. One artifact’s supply chain is a combination of its dependencies’

supply chains plus its own sources and builds.

| Term |

Description |

Example |

| Artifact |

An immutable blob of data; primarily refers to software, but SLSA can be used for any artifact. |

A file, a git commit, a directory of files (serialized in some way), a container image, a firmware image. |

| Attestation |

An authenticated statement (metadata) about a software artifact or collection of software artifacts. |

A signed SLSA Provenance file. |

| Source |

Artifact that was directly authored or reviewed by persons, without modification. It is the beginning of the supply chain; we do not trace the provenance back any further. |

Git commit (source) hosted on GitHub (platform). |

| Build |

Process that transforms a set of input artifacts into a set of output artifacts. The inputs may be sources, dependencies, or ephemeral build outputs. |

.travis.yml (process) run by Travis CI (platform). |

| Package |

Artifact that is “published” for use by others. In the model, it is always the output of a build process, though that build process can be a no-op. |

Docker image (package) distributed on DockerHub (platform). A ZIP file containing source code is a package, not a source, because it is built from some other source, such as a git commit. |

| Dependency |

Artifact that is an input to a build process but that is not a source. In the model, it is always a package. |

Alpine package (package) distributed on Alpine Linux (platform). |

Build model

We model a build as running on a multi-tenant platform, where each execution is

independent. A tenant defines the build by specifying parameters through some

sort of external interface, often including a reference to a configuration file

in source control. The platform then runs the build by interpreting the

parameters, fetching some initial set of dependencies, initializing the build

environment, and then starting execution. The build then performs arbitrary

steps, possibly fetching additional dependencies, and outputs one or more

artifacts. Finally, for SLSA Build L2+, the platform outputs provenance

describing this whole process.

| Primary Term |

Description |

| Platform |

System that allows tenants to run builds. Technically, it is the transitive closure of software and services that must be trusted to faithfully execute the build. It includes software, hardware, people, and organizations. |

| Build |

Process that converts input sources and dependencies into output artifacts, defined by the tenant and executed within a single environment on a platform. |

| Steps |

The set of actions that comprise a build, defined by the tenant. |

| Environment |

Machine, container, VM, or similar in which the build runs, initialized by the platform. In the case of a distributed build, this is the collection of all such machines/containers/VMs that run steps. |

| External parameters |

The set of top-level, independent inputs to the build, specified by a tenant and used by the platform to initialize the build. |

| Dependencies |

Artifacts fetched during initialization or execution of the build process, such as configuration files, source artifacts, or build tools. |

| Outputs |

Collection of artifacts produced by the build. |

| Provenance |

Attestation (metadata) describing how the outputs were produced, including identification of the platform and external parameters. |

Notably, there is no formal notion of “source” in the build model, just

parameters and dependencies. Most build platforms have an explicit “source”

artifact to be built, which is often a git repository; in the build model, the

reference to this artifact is a parameter while the artifact itself is a

dependency.

For examples on how this model applies to real-world build systems, see index

of build types.

Package model

Software is distributed in identifiable units called packages

according the the rules and conventions of a package ecosystem.

Examples of formal ecosystems include Python/PyPA,

Debian/Apt, and

OCI, while examples of

informal ecosystems include links to files on a website or distribution of

first-party software within a company.

Abstractly, a consumer locates software within an ecosystem by asking a

package registry to resolve a mutable package name into an

immutable package artifact. To publish a package

artifact, the software producer asks the registry to update this mapping to

resolve to the new artifact. The registry represents the entity or entities with

the power to alter what artifacts are accepted by consumers for a given package

name. For example, if consumers only accept packages signed by a particular

public key, then it is access to that public key that serves as the registry.

The package name is the primary security boundary within a package ecosystem.

Different package names represent materially different pieces of

software—different owners, behaviors, security properties, and so on.

Therefore, the package name is the primary unit being protected in SLSA.

It is the primary identifier to which consumers attach expectations.

| Term |

Description |

| Package |

An identifiable unit of software intended for distribution, ambiguously meaning either an “artifact” or a “package name”. Only use this term when the ambiguity is acceptable or desirable. |

| Package artifact |

A file or other immutable object that is intended for distribution. |

| Package ecosystem |

A set of rules and conventions governing how packages are distributed, including how clients resolve a package name into one or more specific artifacts. |

| Package manager client |

Client-side tooling to interact with a package ecosystem. |

| Package name |

The primary identifier for a mutable collection of artifacts that all represent different versions of the same software. This is the primary identifier that consumers use to obtain the software. A package name is specific to an ecosystem + registry, has a maintainer, is more general than a specific hash or version, and has a “correct” source location. A package ecosystem may group package names into some sort of hierarchy, such as the Group ID in Maven, though SLSA does not have a special term for this. |

| Package registry |

An entity responsible for mapping package names to artifacts within a packaging ecosystem. Most ecosystems support multiple registries, usually a single global registry and multiple private registries. |

| Publish [a package] |

Make an artifact available for use by registering it with the package registry. In technical terms, this means associating an artifact to a package name. This does not necessarily mean making the artifact fully public; an artifact may be published for only a subset of users, such as internal testing or a closed beta. |

Ambiguous terms to avoid:

- Package repository — Could mean either package registry or package name,

depending on the ecosystem. To avoid confusion, we always use “repository”

exclusively to mean “source repository”, where there is no ambiguity.

- Package manager (without “client”) — Could mean either package

ecosystem, package registry, or client-side tooling.

Mapping to real-world ecosystems

Most real-world ecosystems fit the package model above but use different terms.

The table below attempts to document how various ecosystems map to the SLSA

Package model. There are likely mistakes and omissions; corrections and

additions are welcome!

Notes:

- Go uses a significantly different distribution model than other ecosystems.

In go, the package name is a source repository URL. While clients can fetch

directly from that URL—in which case there is no “package” or

“registry”—they usually fetch a zip file from a module proxy. The module

proxy acts as both a builder (by constructing the package artifact from

source) and a registry (by mapping package name to package artifact). People

trust the module proxy because builds are independently reproducible and a

checksum database guarantees that all clients receive the same artifact

for a given URL.

Verification model

Verification in SLSA is performed in two ways. Firstly, the build system is

certified to ensure conformance with the requirements at the level claimed by

the build system. This certification should happen on a recurring cadence with

the outcomes published by the platform operator for their users to review and

make informed decisions about which builders to trust.

Secondly, artifacts are verified to ensure they meet the producer defined

expectations of where the package source code was retrieved from and on what

build system the package was built.

| Term |

Description |

| Expectations |

A set of constraints on the package’s provenance metadata. The package producer sets expectations for a package, whether explicitly or implicitly. |

| Provenance verification |

Artifacts are verified by the package ecosystem to ensure that the package’s expectations are met before the package is used. |

| Build system certification |

Build systems are certified for their conformance to the SLSA requirements at the stated level. |

The examples below suggest some ways that expectations and verification may be

implemented for different, broadly defined, package ecosystems.

Example: Small software team

| Term |

Example |

| Expectations |

Defined by the producer’s security personnel and stored in a database. |

| Provenance verification |

Performed automatically on cluster nodes before execution by querying the expectations database. |

| Build system certification |

The build system implementer follows secure design and development best practices, does annual penetration testing exercises, and self-certifies their conformance to SLSA requirements. |

Example: Open source language distribution

| Term |

Example |

| Expectations |

Defined separately for each package and stored in the package registry. |

| Provenance verification |

The language distribution registry verifies newly uploaded packages meet expectations before publishing them. Further, the package manager client also verifies expectations prior to installing packages. |

| Build system certification |

Performed by the language ecosystem packaging authority. |

Security levels

SLSA is organized into a series of levels that provide increasing supply chain

security guarantees. This gives you confidence that software hasn’t been

tampered with and can be securely traced back to its source.

This section is a descriptive overview of the SLSA levels and tracks, describing

their intent. For the prescriptive requirements for each level, see

Requirements. For a general overview of SLSA, see

About SLSA.

Levels and tracks

SLSA levels are split into tracks. Each track has its own set of levels that

measure a particular aspect of supply chain security. The purpose of tracks is

to recognize progress made in one aspect of security without blocking on an

unrelated aspect. Tracks also allow the SLSA spec to evolve: we can add more

tracks without invalidating previous levels.

| Track/Level |

Requirements |

Benefits |

| Build L0 |

(none) |

(n/a) |

| Build L1 |

Attestation showing that the package was built as expected |

Documentation, mistake prevention, inventorying |

| Build L2 |

Signed attestation, generated by a hosted build service |

Reduced attack surface, weak tamper protection |

| Build L3 |

Hardened build service |

Strong tamper protection |

Note: The previous version of the specification used a single unnamed track,

SLSA 1–4. For version 1.0 the Source aspects were removed to focus on the

Build track. A Source track may be added in future versions.

Build track

The SLSA build track describes the level of protection against tampering

during or after the build, and the trustworthiness of provenance metadata.

Higher SLSA build levels provide increased confidence that a package truly came

from the correct sources, without unauthorized modification or influence.

TODO: Add a diagram visualizing the following.

Summary of the build track:

- Set project-specific expectations for how the package should be built.

- Generate a provenance attestation automatically during each build.

- Automatically verify that each package’s provenance meets expectations

before allowing its publication and/or consumption.

What sets the levels apart is how much trust there is in the accuracy of the

provenance and the degree to which adversaries are detected or prevented from

tampering with the package. Higher levels require hardened builds and protection

against more sophisticated adversaries.

Each ecosystem (for open source) or organization (for closed source) defines

exactly how this is implemented, including: means of defining expectations, what

provenance format is accepted, whether reproducible builds are used, how

provenance is distributed, when verification happens, and what happens on

failure. Guidelines for implementers can be found in the

requirements.

Build L0: No guarantees

- Summary

-

No requirements—L0 represents the lack of SLSA.

- Intended for

-

Development or test builds of software that are built and run on the same

machine, such as unit tests.

- Requirements

-

n/a

- Benefits

-

n/a

Build L1: Provenance exists

- Summary

-

Package has a provenance attestation showing how it was built, and a downstream

system automatically verifies that packages were built as expected. Prevents

mistakes but is trivial to bypass or forge.

- Intended for

-

Projects and organizations wanting to easily and quickly gain some benefits of

SLSA—other than tamper protection—without changing their build workflows.

- Requirements

-

-

Up front, the package producer defines how the package is expected to be

built, including the canonical source repository and build command.

-

On each build, the release process automatically generates and distributes a

provenance attestation describing how the artifact was actually built,

including: who built the package (person or system), what process/command

was used, and what the input artifacts were.

-

Downstream tooling automatically verifies that the artifact’s provenance

exists and matches the expectation.

- Benefits

-

-

Makes it easier for both producers and consumers to debug, patch, rebuild,

and/or analyze the software by knowing its precise source version and build

process.

-

Prevents mistakes during the release process, such as building from a commit

that is not present in the upstream repo.

-

Aids organizations in creating an inventory of software and build systems

used across a variety of teams.

- Notes

-

- Provenance may be incomplete and/or unsigned at L1. Higher levels require

more complete and trustworthy provenance.

Build L2: Build service

- Summary

-

Forging the provenance or evading verification requires an explicit “attack”,

though this may be easy to perform. Deters unsophisticated adversaries or those

who face legal or financial risk.

In practice, this means that builds run on a hosted service that generates and

signs the provenance.

- Intended for

-

Projects and organizations wanting to gain moderate security benefits of SLSA by

switching to a hosted build service, while waiting for changes to the build

service itself required by Build L3.

- Requirements

-

All of Build L1, plus:

-

The build runs on a hosted build service that generates and signs the

provenance itself. This may be the original build, an after-the-fact

reproducible build, or some equivalent system that ensures the

trustworthiness of the provenance.

-

Downstream verification of provenance includes validating the authenticity

of the provenance attestation.

- Benefits

-

All of Build L1, plus:

-

Prevents tampering after the build through digital signatures.

-

Deters adversaries who face legal or financial risk by evading security

controls, such as employees who face risk of getting fired.

-

Reduces attack surface by limiting builds to specific build services that

can be audited and hardened.

-

Allows large-scale migration of teams to supported build services early

while further hardening work (Build L3) is done in parallel.

Build L3: Hardened builds

- Summary

-

Forging the provenance or evading verification requires exploiting a

vulnerability that is beyond the capabilities of most adversaries.

In practice, this means that builds run on a hardened build service that offers

strong tamper protection.

- Intended for

-

Most software releases. Build L3 usually requires significant changes to

existing build services.

- Requirements

-

All of Build L2, plus:

- Benefits

-

All of Build L2, plus:

-

Prevents tampering during the build—by insider threats, compromised

credentials, or other tenants.

-

Greatly reduces the impact of compromised package upload credentials by

requiring attacker to perform a difficult exploit of the build process.

-

Provides strong confidence that the package was built from the official

source and build process.

Producing artifacts

This section covers the detailed technical requirements for producing artifacts at

each SLSA level. The intended audience is system implementers and security

engineers.

For an informative description of the levels intended for all audiences, see

Levels. For background, see Terminology. To

better understand the reasoning behind the requirements, see

Threats and mitigations.

The key words “MUST”, “MUST NOT”, “REQUIRED”, “SHALL”, “SHALL NOT”, “SHOULD”,

“SHOULD NOT”, “RECOMMENDED”, “MAY”, and “OPTIONAL” in this document are to be

interpreted as described in RFC 2119.

Overview

Build levels

In order to produce artifacts with a specific build level, responsibility is

split between the Producer and

Build system. The build system MUST strengthen the security controls in

order to achieve a specific level while the producer MUST choose and adopt a

build system capable of achieving a desired build level, implementing any

controls as specified by the chosen system.

Security Best Practices

While the exact definition of what constitutes a secure system is beyond the

scope of this specification, all implementations MUST use industry security

best practices to be conformant to this specification. This includes, but is

not limited to, using proper access controls, securing communications,

implementing proper management of cryptographic secrets, doing frequent updates,

and promptly fixing known vulnerabilities.

Various relevant standards and guides can be consulted for that matter such as

the CIS Critical Security

Controls.

Producer

A package’s producer is the organization that owns and releases the

software. It might be an open-source project, a company, a team within a

company, or even an individual.

NOTE: There were more requirements for producers in the initial

draft version (v0.1) which impacted

how a package can be built. These were removed in the v1.0 specification and

will be reassessed and re-added as indicated in the

future directions.

Choose an appropriate build system

The producer MUST select a build system that is capable of reaching their

desired SLSA Build Level.

For example, if a producer wishes to produce a Build Level 3 artifact, they MUST

choose a builder capable of producing Build Level 3 provenance.

Follow a consistent build process

The producer MUST build their artifact in a consistent

manner such that verifiers can form expectations about the build process. In

some implemenatations, the producer MAY provide explicit metadata to a verifier

about their build process. In others, the verifier will form their expectations

implicitly (e.g. trust on first use).

If a producer wishes to distribute their artifact through a package ecosystem

that requires explicit metadata about the build process in the form of a

configuration file, the producer MUST complete the configuration file and keep

it up to date. This metadata might include information related to the artifact’s

source repository and build parameters.

Distribute provenance

The producer MUST distribute provenance to artifact consumers. The producer

MAY delegate this responsibility to the

package ecosystem, provided that the package ecosystem is capable of

distributing provenance.

Build system

A package’s build system is the infrastructure used to transform the

software from source to package. This includes the transitive closure of all

hardware, software, persons, and organizations that can influence the build. A

build system is often a hosted, multi-tenant build service, but it could be a

system of multiple independent rebuilders, a special-purpose build system used

by a single software project, or even an individual’s workstation. Ideally, one

build system is used by many different software packages so that consumers can

minimize the number of trusted systems. For more background,

see Build Model.

The build system is responsible for providing two things: provenance

generation and isolation between builds. The Build level describes

the degree to which each of these properties is met.

Provenance generation

The build system is responsible for generating provenance describing how the

package was produced.

The SLSA Build level describes the overall provenance integrity according to

minimum requirements on its:

- Completeness: What information is contained in the provenance?

- Authenticity: How strongly can the provenance be tied back to the builder?

- Accuracy: How resistant is the provenance generation to tampering within

the build process?

| Requirement | Description | L1 | L2 | L3

|

|---|

| Provenance Exists |

The build process MUST generate provenance that unambiguously identifies the

output package and describes how that package was produced.

The format MUST be acceptable to the

package ecosystem and/or consumer. It

is RECOMMENDED to use the SLSA Provenance format and associated suite

because it is designed to be interoperable, universal, and unambiguous when

used for SLSA. See that format’s documentation for requirements and

implementation guidelines. If using an alternate format, it MUST contain the

equivalent information as SLSA Provenance at each level and SHOULD be

bi-directionally translatable to SLSA Provenance.

- Completeness: Best effort. The provenance at L1 SHOULD contain sufficient

information to catch mistakes and simulate the user experience at higher

levels in the absence of tampering. In other words, the contents of the

provenance SHOULD be the same at all Build levels, but a few fields MAY be

absent at L1 if they are prohibitively expensive to implement.

- Authenticity: No requirements.

- Accuracy: No requirements.

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓

|

| Provenance is Authentic |

Authenticity: Consumers MUST be able to validate the authenticity of the

provenance attestation in order to:

- Ensure integrity: Verify that the digital signature of the provenance

attestation is valid and the provenance was not tampered with after the

build.

- Define trust: Identify the build system and other entities that are

necessary to trust in order to trust the artifact they produced.

This SHOULD be through a digital signature from a private key accessible only to

the service that generated the provenance attestation.

This allows the consumer to trust the contents of the provenance attestation,

such as the identity of the build system.

Accuracy: The provenance MUST be generated by the build system (i.e. within

the trust boundary identified in the provenance) and not by a tenant of the

build system (i.e. outside the trust boundary).

- The data in the provenance MUST be obtained from the build service, either

because the generator is the build service or because the provenance

generator reads the data directly from the build service.

- The build system MUST have some security control to prevent tenants from

tampering with the provenance. However, there is no minimum bound on the

strength. The purpose is to deter adversaries who might face legal or

financial risk from evading controls.

Completeness: SHOULD be complete.

- There MAY be external parameters that are not sufficiently captured in

the provenance.

- Completeness of resolved dependencies is best effort.

| | ✓ | ✓

|

| Provenance is Unforgeable |

Accuracy: Provenance MUST be strongly resistant to forgery by tenants.

- Any secret material used for authenticating the provenance, for example the

signing key used to generate a digital signature, MUST be stored in a secure

management system appropriate for such material and accessible only to the

build service account.

- Such secret material MUST NOT be accessible to the environment running

the user-defined build steps.

- Every field in the provenance MUST be generated or verified by the build

service in a trusted control plane. The user-controlled build steps MUST

NOT be able to inject or alter the contents.

Completeness: SHOULD be complete.

- External parameters MUST be fully enumerated.

- Completeness of resolved dependencies is best effort.

Note: This requirement was called “non-falsifiable” in the initial

draft version (v0.1).

| | | ✓

|

Isolation strength

The build system is responsible for isolating between builds, even within the

same tenant project. In other words, how strong of a guarantee do we have that

the build really executed correctly, without external influence?

The SLSA Build level describes the minimum bar for isolation strength. For more

information on assessing a build system’s isolation strength, see

Verifying build systems.

| Requirement | Description | L1 | L2 | L3

|

|---|

| Build service

|

All build steps ran using some build service, not on an individual’s

workstation.

Examples: GitHub Actions, Google Cloud Build, Travis CI.

| | ✓ | ✓

|

| Isolated

|

The build service ensured that the build steps ran in an isolated environment,

free of unintended external influence. In other words, any external influence on

the build was specifically requested by the build itself. This MUST hold true

even between builds within the same tenant project.

The build system MUST guarantee the following:

- It MUST NOT be possible for a build to access any secrets of the build

service, such as the provenance signing key, because doing so would

compromise the authenticity of the provenance.

- It MUST NOT be possible for two builds that overlap in time to influence one

another, such as by altering the memory of a different build process running

on the same machine.

- It MUST NOT be possible for one build to persist or influence the build

environment of a subsequent build. In other words, an ephemeral build

environment MUST be provisioned for each build.

- It MUST NOT be possible for one build to inject false entries into a build

cache used by another build, also known as “cache poisoning”. In other

words, the output of the build MUST be identical whether or not the cache is

used.

- The build system MUST NOT open services that allow for remote influence

unless all such interactions are captured as

externalParameters in the

provenance.

There are no sub-requirements on the build itself. Build L3 is limited to

ensuring that a well-intentioned build runs securely. It does not require that

build systems prevent a producer from performing a risky or insecure build. In

particular, the “Isolated” requirement does not prohibit a build from calling

out to a remote execution service or a “self-hosted runner” that is outside the

trust boundary of the build platform.

NOTE: This requirement was split into “Isolated” and “Ephemeral Environment”

in the initial draft version (v0.1).

NOTE: This requirement is not to be confused with “Hermetic”, which roughly

means that the build ran with no network access. Such a requirement requires

substantial changes to both the build system and each individual build, and is

considered in the future directions.

| | | ✓

|

Verifying build systems

The provenance consumer is responsible for deciding whether they trust a builder to produce SLSA Build L3 provenance. However, assessing Build L3 capabilities requires information about a builder’s construction and operating procedures that the consumer cannot glean from the provenance itself. To aid with such assessments, we provide a common threat model and builder model for reasoning about builders’ security. We also provide a questionnaire that organizations can use to describe their builders to consumers along with sample answers that do and do not satisfy the SLSA Build L3 requirements.

Threat Model

Attacker Goal

The attacker’s primary goal is to tamper with a build to create unexpected, vulnerable, or malicious behavior in the output artifact while avoiding detection. Their means of doing so is generating build provenance that does not faithfully represent the built artifact’s origins or build process.

More formally, if a build with external parameters P would produce an artifact with binary hash X and a build with external parameters P’ would produce an artifact with binary hash Y, they wish to produce provenance indicating a build with external parameters P produced an artifact with binary hash Y.

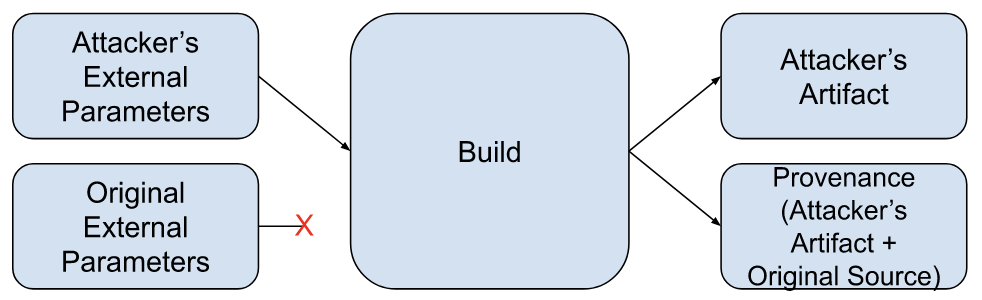

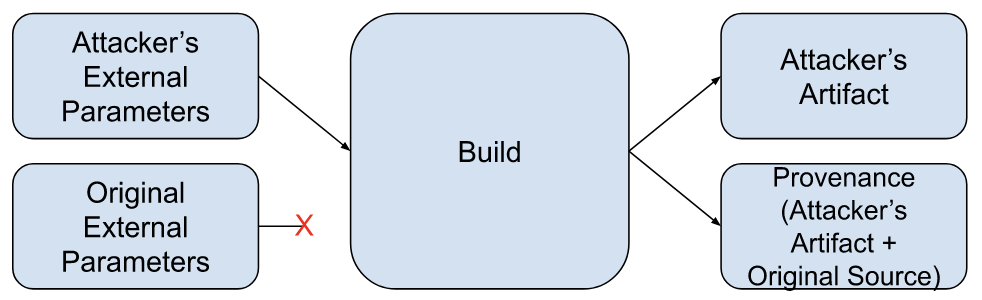

This diagram represents a successful attack:

Note: Platform abuse (e.g. running non-build workloads) and attacks against builder availability are out of scope of this document.

TODO: Align/cross-reference with SLSA Provenance Model.

TODO: Redraw diagrams in the style used by the rest of the site.

Types of attackers

We consider three attacker profiles differentiated by the attacker’s capabilities and privileges as related to the build they wish to subvert (the “target build”).

TODO: Tie attack profiles into the rest of this section.

Project contributors

Capabilities:

- Create builds on the build service. These are the attacker’s controlled builds.

- Modify one or more controlled builds’ external parameters.

- Modify one or more controlled builds’ environments and run arbitrary code inside those environments.

- Read the target build’s source repo.

- Fork the target build’s source repo.

- Modify a fork of the target build’s source repo and build from it.

Project maintainer

Capabilities:

- All listed under “project contributors”.

- Create new builds under the target build’s project or identity.

- Modify the target build’s source repo and build from it.

- Modify the target build’s configuration.

Build service admin

Capabilities:

- All listed under “project contributors” and “project maintainers”.

- Run arbitrary code on the build service.

- Read and modify network traffic.

- Access the control plane’s cryptographic secrets.

- Remotely access build executors (e.g. via SSH).

TODO: List other high-privilege capabilities.

TODO: Maybe differentiate between unilateral and non-unilateral privileges.

Build Model

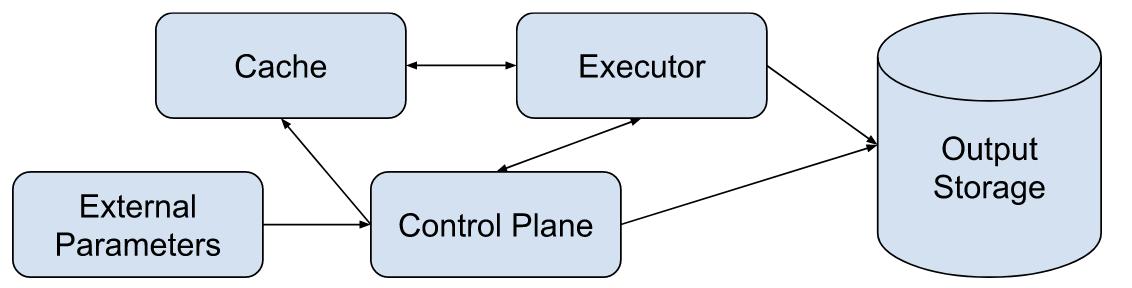

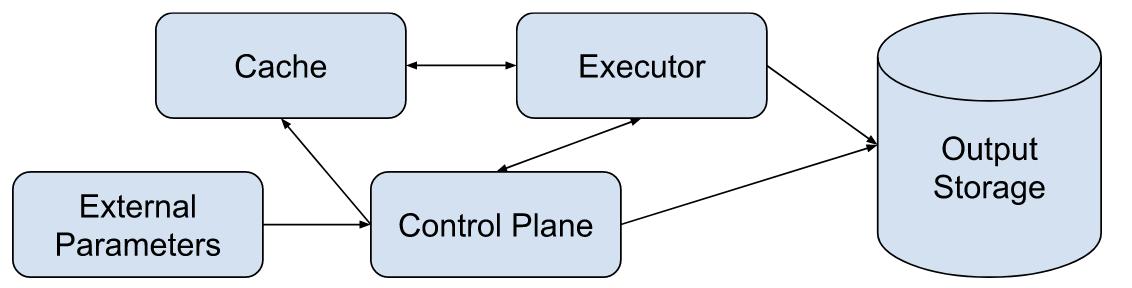

The build model consists of five components: parameters, the control plane, one or more build executors, a build cache, and output storage. The data flow between these components is shown in the diagram below.

TODO: Align with provenance and build models.

The following subsections detail each element of the build model and prompts for assessing its ability to produce SLSA Build L3 provenance.

External Parameters

External parameters are the external interface to the builder and include all inputs to the build process. Examples include the source to be built, the build definition/script to be executed, user-provided instructions to the control plane for how to create the build executor (e.g. which operating system to use), and any additional user-provided strings.

Prompts for Assessing External Parameters

- How does the control plane process user-provided external parameters? Examples: sanitizing, parsing, not at all

- Which external parameters are processed by the control plane and which are processed by the executor?

- What sort of external parameters does the control plane accept for executor configuration?

- How do you ensure that all external parameters are represented in the provenance?

- How will you ensure that future design changes will not add additional external parameters without representing them in the provenance?

Control Plane

The control plane is the build system component that orchestrates each independent build execution. It is responsible for setting up each build and cleaning up afterwards. At SLSA Build L2+ the control plane generates and signs provenance for each build performed on the build service. The control plane is operated by one or more administrators, who have privileges to modify the control plane.

Prompts for Assessing Control Planes

Executor

The build executor is the independent execution environment where the build takes place. Each executor must be isolated from the control plane and from all other executors, including executors running builds from the same build user or project. Build users are free to modify the environment inside the executor arbitrarily. Build executors must have a means to fetch input artifacts (source, dependencies, etc).

Prompts for Assessing Executors

-

Isolation technologies

- How are executors isolated from the control plane and each other? Examples: VMs, containers, sandboxed processes

- How have you hardened your executors against malicious tenants? Examples: configuration hardening, limiting attack surface

- How frequently do you update your isolation software?

- What is your process for responding to vulnerability disclosures? What about vulnerabilities in your dependencies?

- What prevents a malicious build from gaining persistence and influencing subsequent builds?

-

Creation and destruction

- What tools and environment are available in executors on creation? How were the elements of this environment chosen? Examples: A minimal Linux distribution with its package manager, OSX with HomeBrew

- How long could a compromised executor remain active in the build system?

-

Network access

- Are executors able to call out to remote execution? If so, how do you prevent them from tampering with the control plane or other executors over the network?

- Are executors able to open services on the network? If so, how do you prevent remote interference through these services?

Cache

Builders may have zero or more caches to store frequently used dependencies. Build executors may have either read-only or read-write access to caches.

Prompts for Assessing Caches

- What sorts of caches are available to build executors?

- How are those caches populated?

- How are cache contents validated before use?

Output Storage

Output Storage holds built artifacts and their provenance. Storage may either be shared between build projects or allocated separately per-project.

Prompts for Assessing Output Storage

- How do you prevent builds from reading or overwriting files that belong to another build? Example: authorization on storage

- What processing, if any, does the control plane do on output artifacts?

Builder Evaluation

Organizations can either self-attest to their answers or seek an audit/certification from a third party. Questionnaires for self-attestation should be published on the internet. Questionnaires for third-party certification need not be published. All provenance generated by L3+ builders must contain a unforgeable attestation of the builder’s L3+ capabilities with a limited validity period. Any secret materials used to prove the unforgeability of the attestation must belong to the attesting party.

TODO: Add build system attestation spec

Verifying artifacts

SLSA uses provenance to indicate whether an artifact is authentic or not, but

provenance doesn’t do anything unless somebody inspects it. SLSA calls that

inspection verification, and this section describes how to verify artifacts and

their SLSA provenance.

This section is divided into several subsections. The first discusses choices

software distribution and/or deployment system implementers must make regarding

verifying provenance. The second describes how to set the expectations used to

verify provenance. The third describes the procedure for verifying an artifact

and its provenance against a set of expectations.

Architecture options

System implementers decide which part(s) of the system will verify provenance:

the package ecosystem at upload time, the consumers at download time, or via a

continuous monitoring system. Each option comes with its own set of

considerations, but all are valid. The options are not mutually exclusive, but

at least one part of a SLSA-conformant system must verify provenance.

More than one component can verify provenance. For example, if a package

ecosystem verifies provenance, then consumers who get artifacts from that

package ecosystem do not have to verify provenance. Consumers can do so with

client-side verification tooling or by polling a monitor, but there is no

requirement that they do so.

Package ecosystem

⚠ TODO Update this subsection to use Package model terminology.

A package ecosystem is a set of conventions and

tooling for package distribution. Every package has an ecosystem, whether it is

formal or ad-hoc. Some ecosystems are formal, such as language distribution

(e.g. Python/PyPA), operating system distribution (e.g.

Debian/Apt), or artifact

distribution (e.g. OCI).

Other ecosystems are informal, such as a convention used within a company. Even

ad-hoc distribution of software, such as through a link on a website, is

considered an “ecosystem”. For more background, see

Package Model.

During package upload, a package ecosystem can ensure that the artifact’s

provenance matches the known expectations for that package name before accepting

it into the registry. If possible, system implementers SHOULD prefer this option

because doing so benefits all of the package ecosystem’s clients.

The package ecosystem is responsible for reliably redistributing

artifacts and provenance, making the producers’ expectations available to consumers,

and providing tools to enable safe artifact consumption (e.g. whether an artifact

meets its producer’s expectations).

Consumer

A package’s consumer is the organization or individual that uses the

package.

Consumers can set their own expectations for artifacts or use default

expectations provided by the package producer and/or package ecosystem.

In this situation, the consumer uses client-side verification tooling to ensure

that the artifact’s provenance matches their expectations for that package

before use (e.g. during installation or deployment). Client-side verification

tooling can be either standalone, such as

slsa-verifier, or built into

the package ecosystem client.

Monitor

A monitor is a service that verifies provenance for a set

of packages and publishes the result of that verification. The set of

packages verified by a monitor is arbitrary, though it MAY mimic the set

of packages published through one or more package ecosystems. The monitor

MUST publish its expectations for all the packages it verifies.

Consumers can continuously poll a monitor to detect artifacts that

do not meet the monitor’s expectations. Detecting artifacts that fail

verification is of limited benefit unless a human or another part of the system

responds to the failed verification.

Setting Expectations

Expectations are known provenance values that indicate the

corresponding artifact is authentic. For example, a package ecosystem may

maintain a mapping between package names and their canonical source

repositories. That mapping constitutes a set of expectations. The package

ecosystem tooling tests those expectations during upload to ensure all packages

in the ecosystem are built from their canonical source repo, which

indicates their authenticity.

Expectations MUST be sufficient to detect or prevent an adversary from injecting

unofficial behavior into the package. Example threats in this

category include building from an unofficial fork or abusing a build parameter

to modify the build. Usually expectations identify the canonical source

repository (which is the main external parameter) and any other

security-relevant external parameters.

It is important to note that expectations are tied to a package name, whereas

provenance is tied to an artifact. Different versions of the same package name

may have different artifacts and therefore different provenance. Similarly, an

artifact may have different names in different package ecosystems but use the same

provenance file.

Package ecosystems

using the RECOMMENDED suite of attestation

formats SHOULD list the package name in the provenance attestation statement’s

subject field, though the precise semantics for binding a package name to an

artifact are defined by the package ecosystem.

| Requirement | Description | L1 | L2 | L3

|

|---|

| Expectations known

|

The package ecosystem MUST ensure that expectations are defined for the package before it is made available to package ecosystem users.

There are several approaches a package ecosystem could take to setting expectations, for example:

- Requiring the producer to set expectations when registering a new package

in the package ecosystem.

- Using the values from the package’s provenance during its initial

publication (trust on first use).

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓

|

| Changes authorized

|

The package ecosystem MUST ensure that any changes to expectations are

authorized by the package’s producer. This is to prevent a malicious actor

from updating the expectations to allow building and publishing from a fork

under the malicious actor’s control. Some ways this could be achieved include:

- Requiring two authorized individuals from the package producer to approve

the change.

- Requiring consumers to approve changes, in a similar fashion to how SSH

host fingerprint changes have to be approved by users.

- Disallowing changes altogether, for example by binding the package name to

the source repository.

| | ✓ | ✓

|

How to verify

Verification MUST include the following steps:

- Ensuring that the builder identity is one of those in the map of trusted

builder id’s to SLSA level.

- Verifying the signature on the provenance envelope.

- Ensuring that the values for

BuildType and ExternalParameters in the

provenance match the known expectations. The package ecosystem MAY allow

an approved list of ExternalParameters to be ignored during verification.

Any unrecognized ExternalParameters SHOULD cause verification to fail.

Note: This subsection assumes that the provenance is in the recommended

provenance format. If it is not, then the verifier must

perform equivalent checks on provenance fields that correspond to the ones

referenced here.

Step 1: Check SLSA Build level

First, check the SLSA Build level by comparing the artifact to its provenance

and the provenance to a preconfigured root of trust. The goal is to ensure that

the provenance actually applies to the artifact in question and to assess the

trustworthiness of the provenance. This mitigates some or all of threats “D”,

“F”, “G”, and “H”, depending on SLSA Build level and where verification happens.

Once, when bootstrapping the verifier:

-

Configure the verifier’s roots of trust, meaning the recognized builder

identities and the maximum SLSA Build level each builder is trusted up to.

Different verifiers might use different roots of trust, but usually a

verifier uses the same roots of trust for all packages. This configuration

is likely in the form of a map from (builder public key identity,

builder.id) to (SLSA Build level) drawn from the SLSA Conformance

Program (coming soon).

Example root of trust configuration

The following snippet shows conceptually how a verifier’s roots of trust

might be configured using made-up syntax.

"slsaRootsOfTrust": [

// A builder trusted at SLSA Build L3, using a fixed public key.

{

"publicKey": "HKJEwI...",

"builderId": "https://somebuilder.example.com/slsa/l3",

"slsaBuildLevel": 3

},

// A different builder that claims to be SLSA Build L3,

// but this verifier only trusts it to L2.

{

"publicKey": "tLykq9...",

"builderId": "https://differentbuilder.example.com/slsa/l3",

"slsaBuildLevel": 2

},

// A builder that uses Sigstore for authentication.

{

"sigstore": {

"root": "global", // identifies fulcio/rekor roots

"subjectAlternativeNamePattern": "https://github.com/slsa-framework/slsa-github-generator/.github/workflows/generator_generic_slsa3.yml@refs/tags/v*.*.*"

}

"builderId": "https://github.com/slsa-framework/slsa-github-generator/.github/workflows/generator_generic_slsa3.yml@refs/tags/v*.*.*",

"slsaBuildLevel": 3,

}

...

],

Given an artifact and its provenance:

- Verify the envelope’s signature using the roots of

trust, resulting in a list of recognized public keys (or equivalent).

- Verify that statement’s

subject matches the digest of

the artifact in question.

- Verify that the

predicateType is https://slsa.dev/provenance/v1?draft.

- Look up the SLSA Build Level in the roots of trust, using the recognized

public keys and the

builder.id, defaulting to SLSA Build L1.

Resulting threat mitigation:

- Threat “D”: SLSA Build L3 requires protection against compromise of the

build process and provenance generation by an external adversary, such as

persistence between builds or theft of the provenance signing key. In other

words, SLSA Build L3 establishes that the provenance is accurate and

trustworthy, assuming you trust the build platform.

- IMPORTANT: SLSA Build L3 does not cover compromise of the build

platform itself, such as by a malicious insider. Instead, verifiers

SHOULD carefully consider which build platforms are added to the roots

of trust. For advice on establishing trust in build platforms, see